Field Report: Comparing bird communities in willow and Miscanthus crop fields

Introduction

This report outlines a three-day bird survey conducted at two farms, one in Devon and the other in Somerset. One farm had a mixed age willow crop, while the other had a miscanthus crop. The aim of the surveys was to record and map the birds seen at each farm to see what benefits each crop may have for different species.

Rationale

Willow and miscanthus are fast-growing crops with a wide range of uses including biofuels. A recent meta-analysis of published scientific papers has shown that the planting of non-food biofuel crops (such as willow, poplar and miscanthus) in areas that were previously arable crops or grassland has a positive effect on bird, invertebrate and plant populations alongside soil microbes (Donnison et al. 2021). There were particularly strong benefits when arable land was converted to biomass crops. Studies in the UK are often limited and focus on younger, establishing crops of Miscanthus (Semere & Slater 2007, Bellamy et al. 2009, Bright et al. 2013). However, studies on willow crops do often reflect how they appeal to different bird populations during different seasons and at different stages of crop rotation (Anderson et al. 2004, Sage et al. 2006, Fry & Slater 2011).

Method

I made single dawn (7:30am to 9:30am) and dusk (2:30pm to 4:30pm) winter visits to one farm with a willow crop and another with a miscanthus crop:

- The mixed variety willow crop covers 3.95 hectares on Umberleigh Barton Farm, aworking mixed farm based in North Devon. It was planted in 2015 and supplies abiomass boiler to supply space and water heating to the various buildings on site.

- The miscanthus crop is grown across 17 hectares to provide heat for poultry barnsat Langaller Farm in Somerset. It is well established and has been grown heresince 2006/07.

The two visits at each farm provided a snapshot into what birds were using the crops between the 23rd and 25th November 2023. The surveys used the Common Bird Census (CBC) method (Williamson & Homes 1964). This is based on a territory-mapping approach, which involves recording all contacts with birds (by sight or sound) on a map of a defined area, during a series of visits throughout the breeding season. Birds were recorded within a 250-metres buffer zone of the two crops.

During the surveys the weather was calm and influenced by cold, northerly air. The temperature started off at 11°C with cloud on the 23rd at Umberleigh Barton Farm, 9°C with clearing skies on the 24th at both locations and dropped to an overnight low of -3°C, clear skies and a hard frost on the 25th at Langaller Farm.

Two 10 minute videos were made during the surveys. These can be viewed at: https://www.biomassconnect.org/news/bird-surveys-on-biomass-plantations/

Results

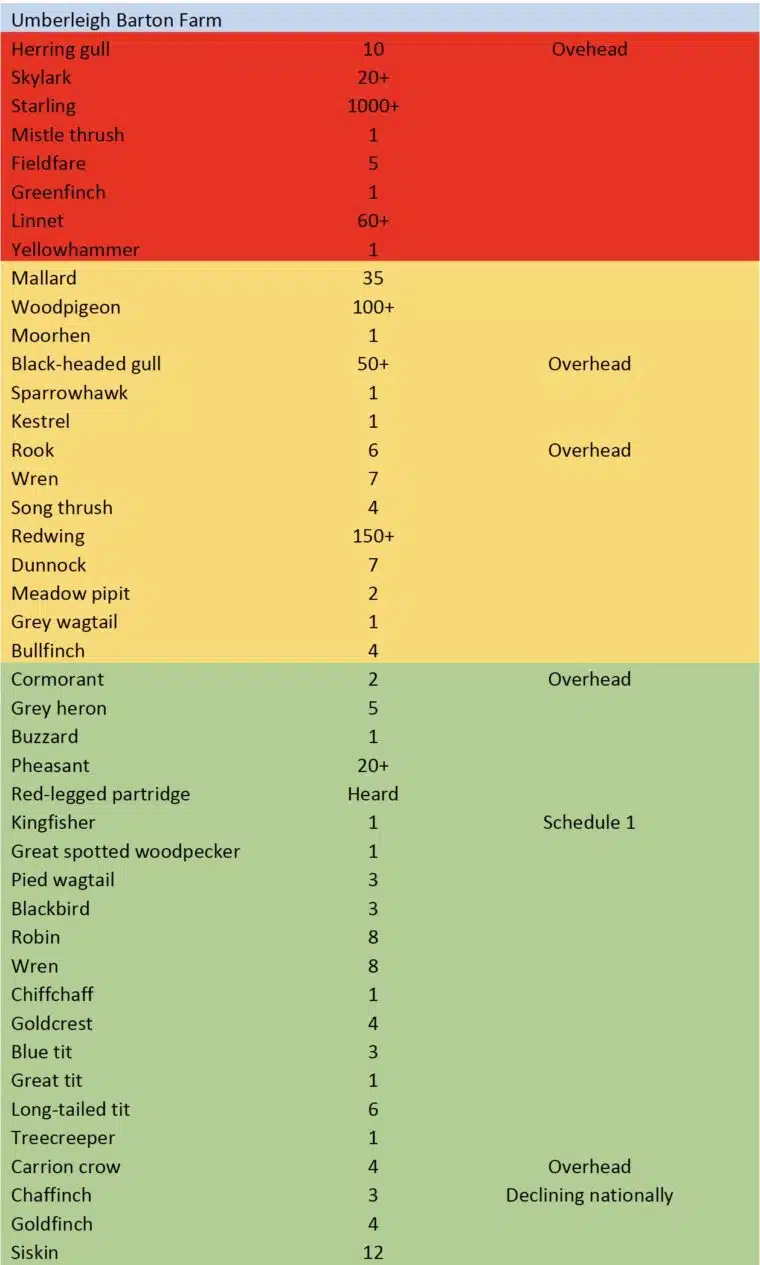

A total of 49 different bird species were recorded on or flying over the two farms. A summary of the species recorded at each location is summarised in Table 1 and Table 2. The colours relate to their conservation status in the UK based on the Birds of Conservation Concern 5 (BOCC5) (Stanbury et al. 2021), where red is of most conservation concern and green is of least concern.

Table 1: A summary of the bird species recorded on or over Umberleigh Barton Farm (willow crop). Red = red listed; orange = amber listed; green = green listed.

Willow Crop

The willow crop and surrounding habitat (within 250 metres) supported 38 species (Table 1 and Figure 1). A further five species flew overhead and were not using the immediate habitat (black-headed gull, herring gull, cormorant, carrion crow and rook). Eleven species were seen or heard in the willow crop included wren, song thrush, blackbird, great tit, blue tit, goldcrest, long-tailed tit, robin, dunnock, siskin and chiffchaff. These species appeared to be penetrating the mixed age willow and could be seen or heard moving deep (10 metres and beyond) into the crop. For example, a flock of long-tailed tits came out from the willow crop and heading into a woodland copse by the railway and song thrushes could be heard calling from deep within the willow. A flock of siskins circled overhead and came down to the tops of the older, mature willow stems. At dusk, 60+ linnets perched on the telegraph wires above one-year old willow stems and dropped down to rest for the night (roost). The adjacent stubble and winter-crop fields had a slightly different suite of bird species compared to the willow crop and the hedgerows. A flock of over 1,000 starlings were feeding in the stubble field by the willow crop and a flock of skylarks were occasionally rising up from this and other nearby fields. The pastoral, grassy fields to the west of the crop were largely devoid of any birdlife.

Miscanthus Crop

The miscanthus crop supported fewer species and the majority of the 28 species recorded were using the adjacent hedgerows, woodland and grassland habitats (see Table 2 and Figure 2). However, nine species were seen using the crop: wren, pied wagtail, song thrush, blackbird, reed bunting, goldcrest, meadow pipit, long-tailed tit and redwing. Most were on the edge of the miscanthus, flying into or out of the crop, presumably looking for food. For example, two goldcrests were foraging in the ancient hedgerow and then flew across to the miscanthus. Wrens and robins were generally crossing between the hedgerow or field margins and spending time on the edge of the miscanthus. At dusk on the second survey for this site over 1,000 pied wagtails flew into roost in one area of the miscanthus. This was situated on a lower slope closer to the farm buildings (see Figure 2). They appeared in flocks – often ten to 20 birds – over a 40-minute period (3:50pm to 4:40pm). A small number of redwings (6+) also appeared to drop down into the miscanthus. Overall, birds seen during the surveys were mostly using the miscanthus, the hedgerows and the patches of woodlands. The pastoral, grassy fields were largely devoid of birdlife aside from the occasional meadow pipit, blackbird or robin, and a stonechat that was moving from fencepost to fencepost by the miscanthus crop.

Discussion

The overall number of individuals (abundance) and diversity of species (richness) of birds differed between the two locations, although both crops supported large numbers of roosting birds – the young willow crop was used by linnets and the miscanthus was used by pied wagtails (and to a lesser degree redwings and reed buntings).

Umberleigh Barton Farm (willow) had a more diverse range of bird species, probably complemented by the mixed farming environment surrounding the willow. It formed part of a continuous mosaic environment. The corridor of trees and scrub along the railway line, hedgerows and stubble fields are complemented by the willow and allow birds to extend their foraging into it. The different stages of willow crop also replicate similar features to traditional coppicing methods that were once abundant across Britain and benefit a range of wildlife (Fuller & Warren 1993, Anderson et al. 2004). Overall, it appeared the willow crop was providing an additional habitat to what was already there and supporting woodland/hedgerow birds. The adjacent stubble and winter-crop fields were occupied by a small number of species – namely starling, skylark and a kestrel – which did not use the willow crop (although skylarks will use willow plantations after they have recently been cut (Sage et al. 2006)). Sage et al. (2006) also found that hedgerows adjacent to a willow crop contained more bird species than hedgerows adjacent to arable crops or grassy fields.

In comparison, Langaller Farm (miscanthus) had a smaller range of bird species, with most of the birds being concentrated in the field edges along the ancient hedgerows and adjacent woodland. This may be because the non-native crop provides less food for birds (Bellamy et al. 2009); examination of the stems and leaves of the miscanthus did not show any damage from insects feeding on it. A study in Ukraine shows that some insect populations – such as aphids, leafhoppers and thrips – are supported by miscanthus (Stefanovska et al. 2017), while another study in the UK shows that where other plants are able to grow in miscanthus plantations – after cropping and in earlier stages of growth – they support higher populations of invertebrates compared to other crops such as reed-canary grass (Semere & Slater 2007). Spiders may still use the stems for making webs and at ground level there are likely to be ground invertebrates such as beetles, slugs, snails, springtails and other soil inverts, although miscanthus supports lower populations of invertebrates – such as spiders, harvestmen and ground beetles – compared to mixed-use arable fields (Williams & Feest 2019). A study by Sage et al. (2010) shows that bird populations can be variable depending on the how the miscanthus grows and whether there are patches of other plants growing (that provide more food for birds). The lower bird abundance and richness in this crop may also be down to the geography of the location. The farm is 180 metres above sea level and many birds may have moved to lower ground where there is more food and slightly warmer temperatures. Despite this lower abundance, it was apparent that while the adjacent pastoral meadows were largely devoid of any birds, the miscanthus did have more birds, albeit concentrated along its edges.

Sage et al. (2010) found a largely neutral effect of miscanthus on woodland and farmland birds, although miscanthus crops often contained low numbers of birds. However, they did find unharvested miscanthus crops held more birds during winter, such as woodcock, blackbirds and reed buntings, compared to comparison plots (arable, grassland and short rotation coppice willow), although there was a lot of variability between the latter. Bellamy et al. (2009) also found miscanthus to have a higher population of birds in winter compared to adjacent wheat crop fields.

The results of these winter ‘snapshot’ bird surveys suggest that while both types of crops support a variety of small birds, the way in which birds use them in late November differs. The willow appears to provide more feeding opportunities throughout its structure, although particularly in the areas two years old or more. They provide gaps for light to reach the ground level and allow a herb-bramble-nettle layer to grow, providing more feeding and nesting opportunities for birds. The miscanthus meanwhile creates favourable cover for roosting pied wagtails and feeding opportunities along its margins. The mature miscanthus develops a thick sward which allows less light to penetrate to the ground level and therefore fewer opportunities for other plants to grow. In some places, where the soil is thin, the miscanthus grows shorter and in patches, allowing shorter, native grasses and other plants to grow. This is likely to be more attractive to invertebrates and feeding birds.

Limitations

The dawn and dusk visits were single, one-off winter visits that provide a snapshot of what is using each crop. We will be repeating the visits in the spring and summer to see how the crops compare. More regular, monthly surveys would need to be conducted to monitor bird populations more accurately over time.

Recommendations

The miscanthus will continue to provide roosting habitat for the pied wagtails until the spring. The birds will start to disperse in March as they take up territory ready for the breeding season. Cutting the miscanthus in April should miss the period in which the birds are using it as a roost (although may affect anything trying to nest in it).

The mixed-age willow will continue to provide roosting habitat for the linnets and the birds are likely to move around as the crop is cut on rotation providing different aged growth, some of which will be to their liking.

Conclusion

The bird surveys conducted at the two farms have provided valuable information about the bird populations in the two areas. The results illustrate how more regular surveys would build a more detailed picture of what and how birds use these crops and how they differ over seasons and years. These in turn can inform and support decisions on how these crops can support nature recovery, carbon sequestration and their use as biofuels.

Photo Credits

Photo credits for Figure 1 and 2

Photos from Flickr (CC BY 2.0): chaffinch by Alan Cleaver; chiffchaff, great spotted woodpecker, house sparrow, long-tailed tit, siskin, stonechat, treecreeper and wren by Caroline Legg; stock dove by Frank Vassen; reed bunting by Gérard Meyer; kestrel by Hari K Patibanda; woodpigeon by Ian Preston; skylark by Imran Shah; goldcrest by Jo Garbutt; kingfisher by Joe M Devereux; sparrowhawk by John Freshney; bullfinch and greenfinch by Luiz Lapa; dunnock and linnet by Nick Goodrum; grey wagtail by Nigel Hoult; meadow pipit by Ron Knight; mistle thrush by Sudge 9000. Photo from Flickr (CC0): pied wagtail by Wildlife Terry. Photo from Pexels: Redwing by Denitsa Kireva; Chaffinch by Phil Mitchel. Other photos: mallard, moorhen and starling by Ed Drewitt.

Satellite images used courtesy of Bing Maps.

References

Anderson, G. Q., Haskins, L. R. & Nelson, S. H. (2004). The effects of bioenergy crops on farmland birds in the United Kingdom: a review of current knowledge and future predictions. In: Biomass and Agriculture: Sustainability, Markets and Policies (eds: K. Parris & D. Poincet). Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, Paris, France, 572, 199-218.

Bellamy, P. E., Croxton, P. J., Heard, M. S., Hinsley, S. A., Hulmes, L., Hulmes, Nuttall, P., Pywell, R.F. & Rothery, P. (2009). The impact of growing miscanthus for biomass on farmland bird populations. Biomass and Bioenergy, 33(2), 191-199.

Bright, J. A., Anderson, G. Q., Mcarthur, T., Sage, R., Stockdale, J., Grice, P. V. & Bradbury, R. B.(2013). Bird use of establishment-stage Miscanthus biomass crops during thebreeding season in England. Bird Study, 60(3), 357-369.

Donnison, C., Holland, R. A., Harris, Z. M., Eigenbrod, F. & Taylor, G. (2021). Land-use change from food to energy: Meta-analysis unravels effects of bioenergy on biodiversity and cultural ecosystem services. Environmental research letters, 16(11), 113005.

Fry, D. A. & Slater, F. M. (2011). Early rotation short rotation willow coppice as a winter food resource for birds. Biomass and Bioenergy, 35(7), 2545-2553.

Fuller, R. J. & Warren, M. S. (1993). Coppiced woodlands: their management for wildlife. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee.

Sage, R., Cunningham, M. & Boatman, N. (2006). Birds in willow short‐rotation coppice compared to other arable crops in central England and a review of bird census data from energy crops in the UK. Ibis, 148, 184-197.

Sage, R., Cunningham, M., Haughton, A.J., Mallott, M.D., Bohan, D.A., Riche, A. & Karp, A., 2010. The environmental impacts of biomass crops: use by birds of miscanthus in summer and winter in southwestern England. Ibis, 152(3), 487-499.

Semere, T. & Slater, F. M. (2007). Ground flora, small mammal and bird species diversity in miscanthus (Miscanthus× giganteus) and reed canary-grass (Phalaris arundinacea) fields. Biomass and Bioenergy, 31(1), 20-29.

Stanbury, A., Eaton, M., Aebischer, N., Balmer, D., Brown, A., Douse, A., Lindley, P., McCulloch, N., Noble, D. & Win, I. (2021). The status of our bird populations: the fifth Birds of Conservation Concern in the United Kingdom, Channel Islands and Isle of Man and second IUCN Red List assessment of extinction risk for Great Britain. British Birds, 114, 723-747.

Stefanovska, T., Pidlisnyuk, V., Lewis, E. & Gorbatenko, A. (2017). Herbivorous insects diversity at miscanthus× giganteus in Ukraine. Agriculture (Pol’nohospodárstvo), 63(1), 23-32.

Williams, M.A. & Feest, A. (2019). The effect of Miscanthus cultivation on the biodiversity of ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae), spiders and harvestmen (Arachnida: Araneae and Opiliones). Agricultural Sciences, 10(7), 903-917.

Williamson, K. & Homes, R. C. (1964). Methods and preliminary results of the Common Birds Census, 1962–63. Bird Study, 11(4), 240-256.